Amazon.com International Sites :

USA, United Kingdom, Germany, France

Books about Persia :

Persia and the Greeks : The Defence of the West C546-478 B.C.

From Ancient Persia To Contemporary Iran:

Seletcted Historical

Babylonia, and Assyria were many centuries old when a vigorous people appeared on the eastern border of the

ancient civilized world. They came from the grasslands of Turkestan in Central Asia with their sheep and horses.

They made their home on the high mountain-walled plateau between the Caspian Sea and the Persian Gulf.

The newcomers called themselves Irani (Aryans) and their new homeland Irania (now Iran). They came

to be called Persians because Greek geographers mistakenly named them after the province Parsa, or Persis, where

their early kings had their capital. The Persians and their close relatives, the Medes, resembled the Semites,

but they spoke a different language.

The Medes and Persians had many nature gods. In the 6th century BC the religious prophet Zoroaster, or Zarathustra,

appeared in the northwest. According to his teachings, there was one supreme god, Ahura Mazda, and there was constant

conflict between Mazda, the spirit of light and of good, and Ahriman, the spirit of darkness, or evil (see Zoroastrianism

and Parsiism).

The Medes, by the 6th century BC, had built a large empire. They ruled the Persians to the east and the Assyrians

to the west. In 550 BC Cyrus the Great of Persia conquered the Medes, then pushed on to further conquests. His

warriors, both Medes and Persians, were fine horsemen, skilled with bow and arrow. They relied upon speed and sharp

attack. Before heavily armored enemy troops could come close, the Persians overwhelmed them with arrows.

By conquering the Medes, King Cyrus acquired Assyria, which the Median King Cyarxes had taken in about 612 BC.

Next Cyrus conquered Lydia, ruled by King Croesus (see Croesus). This victory gave him

possession of the Greek seaboard cities of Asia Minor. In 539 BC proud Babylon, capital of the Chaldean Empire,

surrendered without a fight. With Babylon Cyrus acquired Palestine. He allowed the Jews to return from Babylonian

exile and rebuild their temple in Jerusalem. Turning eastward he spread his empire to the border of India. He was

killed fighting against eastern nomads in 529 BC and was buried in a tomb he had prepared at his capital, Pasargadae.

The ruins still remain. Cyrus' son Cambyses II, who ruled from 529 to 522 BC, successfully crossed the hostile

Sinai Peninsula on his way to conquering Egypt in a short campaign.

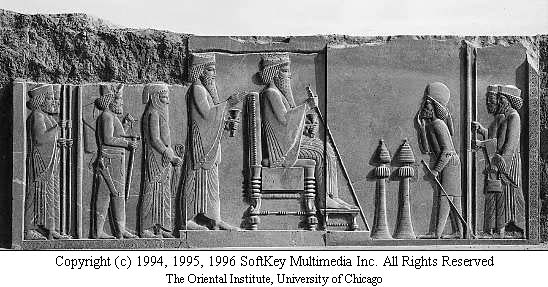

A relief from the treasury wall at Persepolis depicts Darius on his throne, with Xerxes behind him. --The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

Darius, a relative of Cambyses, seized the crown in 522 BC (see Darius I). Under him

the empire flourished. Darius' greatest work was perfecting the system of government begun by Cyrus. The empire

was divided into 20 satrapies, or provinces, each ruled over by a satrap. Officials called the king's eyes made

regular visits to the satrapies and reported to the king. The satrapies furnished soldiers for the king's armies.

Phoenicia, Egypt, and the Greek colonies of Asia Minor also supplied ships and sailors. Each satrap paid a fixed

yearly tribute to Darius the Great.

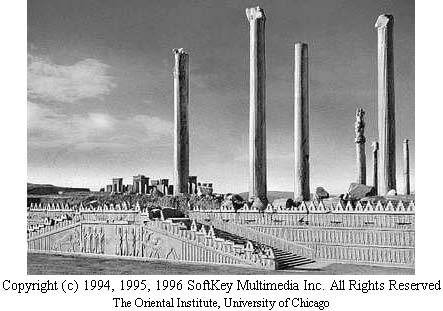

Remains of the ceremonial stairway leading to the royal audience hall of Darius and Xerxes still stand at Persepolis. --The Oriental Institute, University of Chicago

Enormous wealth flowed into the royal treasure houses of Susa, Persepolis, Pasargadae, and Ecbatana. When the king

required money, he minted gold coins. To encourage commerce Darius standardized coins, weights, and measures; built

imperial highways; and completed a canal from the Nile River to the Red Sea. He demanded strict enforcement of

the severe "laws of the Medes and Persians, which altereth not."

Throughout his reign Darius was forced to suppress revolts in the empire. In 500 BC the Greek cities of Asia Minor

rebelled. After putting down this rebellion, Darius turned on Athens to punish it for sending aid to the rebels.

Beaten in the famous battle of Marathon, he prepared another expedition but died in 486 BC before it started.

Xerxes, the son of Darius, ruled from 486 to 465 BC. He was a weak and tyrannical king who began his reign by quelling

rebellions in Egypt and Babylon, then gathered a huge force to overwhelm Greece. It seemed as if the mighty empire

must conquer the small, disunited Greek city-states. Yet Xerxes met disaster at Salamis and Plataea, and his great

army was driven back into Asia (see Persian Wars). This defeat marked the first sign

of decay in the Persian Empire. Persian history for the next 125 years was filled with conspiracies, assassinations,

and the revolts of subject peoples ground down by ruinous taxation. The empire was briefly united under the bloodthirsty

Artaxerxes III (originally Ochus), who ruled from about 359 to 338 BC. He killed many of his relatives and

was then poisoned by his own physician. His son Arses, who succeeded him, was poisoned two years later and all

his children slain.

Darius III, a weakling, was on the throne when Alexander the Great of Macedon led his powerful army into Asia (see

Alexander the Great). In the decisive battle of Issus (333 BC) Alexander captured

the western half of the Persian Empire. Darius fled from the battlefield. He met Alexander again at Arbela (331

BC) and fled once more. Soon afterward one of Darius' own followers murdered him. Thus the ancient line of Persian

kings--the Achaemenian Dynasty--came to an end and with it the Persian Empire. Alexander marched on to Persepolis.

After Alexander's death in 323 BC one of his generals, Seleucus, seized Babylon and founded the Seleucid Dynasty.

Parthia, a small kingdom in northern Persia, broke away, brought Persia under its rule, and built an empire that

extended from the Bolan Pass to the Euphrates River. The Parthians were nomads noted for their splendid horses.

In battle they adopted the ruse of pretending to flee, then wheeling and firing a hail of arrows on their pursuers--hence

the phrase, "Parthian shot." For 300 years they held off Rome.

In AD 226 the Persians again came under a native dynasty, the Sassanids. For four centuries the Sassanids warred

with Rome, with the later Byzantine Empire, and with Huns and Turks. Most of their wars ended disastrously. Outside

Persia they firmly held only Babylon in the lower Tigris-Euphrates Valley.

The Sassanids upheld the Zoroastrian religion, punishing by death those who left the faith. Throughout Persia the

magi, or priests, continued to guard the holy fires of Ahura Mazda. In the 3rd century, however, vigorous new religions

evolved from Zoroastrianism. Mithraism revived Persia's pagan sun god, Mithras, who had been banned by Zoroaster.

Manichaeism (named for its founder Manes, or Mani, the so-called "ambassador of light") sought

to reconcile Zoroastrianism with Christianity in a world religion. Mithraism and

Manichaeism spread from Persia to the Roman Empire, where they conflicted with Christianity.

In the 7th century Persia fell to the conquering armies of Islam. Islamic rule, under the empire of the caliphate,

persisted for seven centuries. It gave the Persians a wholly new religion and altered their way of living. Yet

Persian culture did not die. Islamic rulers of the 'Abbasid caliphate chose Baghdad (then in Persian territory)

as their seat of government. Their court took on a Persian character. The tales of the 'Arabian Nights' unfolded

in the Persian region (see 'Arabian Nights').

Firdawsi, Persia's greatest poet, sang in epic verse of Persia's early kings and inspired miniaturists to make

richly illuminated copies of his legends. Omar Khayyam, best known to the Western world as the author of the 'Rubaiyat',

also made major contributions to astronomy and mathematics.

The Seljuk Turks conquered Persia in the 11th century. In the 13th century Genghis Khan's Mongols devastated the

country (see Genghis Khan). Near the end of the 14th century another Mongol horde

swept over the country, led by Timur Lenk (see Timur Lenk).

At last in 1502 Persian nationalism revived under the Safavid Dynasty. The Safavids claimed descent from Muhammad's

family through his son-in-law 'Ali. They split Persia from the orthodox Muslims, the Sunni, and established Shi'ism

as the state religion. Under Shah 'Abbas (ruled 1588-1629), the greatest of the Safavid Dynasty, Persia reached

a golden age. Art--miniature painting, carpets, tapestries, metalwork, and architecture--flourished during his

reign. Isfahan, the new capital, was embellished with gardens and a great palace, the Hall of Forty Columns.

The Safavids held off the powerful Ottoman Turks, who had taken over the rule of Islam from the Arabs. But Isfahan

fell in 1722 to Afghan tribesmen. After a brief restoration the Safavid Dynasty ended in 1736, when Nader Shah

(ruled 1736-47) seized the throne (see Nader Shah). He freed Persia from the Afghans,

Turks, and Russians and then invaded India. His brief rule was followed by the Zand Dynasty (1750-79) and the Qajar

rulers (1779-1925).

In the 19th century Russia gained control over northern Persia and Great Britain became dominant in the south.

Not until after World War I did the Persian nation once more revive. As a symbol of the rebirth of national feeling,

the government changed the ancient name of Persia to the still more ancient name Iran.

Amazon.com International Sites :